Editor’s note: This is the first story in a multipart series.

The week before Thanksgiving, one of the Marine Corps’ most senior lawyers stood in front of a room full of defense attorneys at Camp Lejeune and discussed changes in sex crime adjudication in the military.

When the colonel began taking questions, a captain with three years of experience as a military defense counsel asked what measures would be in place to protect lawyers and judges like him from improper influences, such as from the chain of command, the media, or Congress.

The colonel conceded that the protections did not exist. Because a military defense is not truly independent from the military chain of command, the military lawyers’ zealous defense of a case could negatively impact their promotions, he said.

“You think you are protected, but that is legal fiction,” said Col. Christopher B. Shaw, the deputy staff judge advocate for the commandant of the Marine Corps — the second-highest position in the Judge Advocate Division — according to sworn affidavits filed by seven Marine officers who witnessed the events.

The colonel squared his shoulders and locked his gaze on the captain, a Marine named Matthew Thomas, who was serving as the lead defense counsel in a contentious homicide trial involving two senior enlisted Marines and a Navy corpsman.

“I know who you are and what cases you are on,” Shaw said, according to Thomas. “You are not protected.”

“Our community is small,” the colonel told the group, “and there are promotion boards, and the lawyer on the promotion board will know you.”

For the defense attorneys standing in the modular trailer, the perceived threat to their careers felt palpable, according to their sworn statements and exclusive interviews with The War Horse. The morning after the meeting, a witness filed a formal complaint to the office of the inspector general of the Marine Corps.

On Dec. 6, fewer than three weeks after Col. Shaw’s comments at Camp Lejeune, the Marine witnesses signed affidavits detailing Shaw’s comments and their detrimental impact on the military defense community. Senior-ranking Marine Corps officials declined to discuss the concerns on the record to The War Horse.

“Col. Shaw has received your numerous interview requests,” wrote Maj. Jim Stenger, a spokesperson for the Corps, in a series of emails. “He has elected not to be interviewed. … We are not currently granting interview requests in this case.”

Shaw’s comments to Capt. Thomas represent one of the clearest examples of how military leaders can abuse their authority both during and outside court proceedings, and they will further degrade trust between uniformed attorneys and service members who face judicial punishments, alleges a defense motion filed with the statements.

The colonel said the Marines — all law-school graduates who have passed a bar exam and whose profession requires that they comprehend complex legal authorities and arguments — simply misunderstood his comments, as well as his ability to influence their careers, the colonel said in two sworn statements to government investigators.

Critics have, for decades, argued for change that could not only have prevented such a conversation but could ultimately have saved the integrity of the Marine Corps legal system.

The colonel’s comments not only undermine the lawyers’ ability to defend their cases, but also harm the entire legal system of the Marine Corps — in addition to the harm the comments could cause them on a personal level, they argued in their affidavits.

Without integrity, the Marine Corps could cause a flood of appeals cases as Marines realize their cases may have been prosecuted in a system not solely based on truth or justice, but on threats to careers or influence from forces unknown to the accused.

“I think the real challenge is that, at some level, the knowledge that your system is unjust can lead units to fracture,” a senior Marine attorney said. “It can directly harm readiness.”

The Marine Corps’ incestuous justice system operates on different levels based on rank and includes a notebook used to track officers’ bad conduct. Repeatedly, the Marine generals and attorneys whose wrongdoings have been documented in the Corps’ own records have been promoted and retired with full military benefits.

“There’s this idea that if you put officer misconduct in the street that it’s going to undermine good order and discipline,” said Eric Montalvo, a retired judge advocate who now serves as a civilian defense attorney.

“Officers get away with more because it’s more frat-like,” Montalvo said. “The officer corps tries to stick together to some extent and take care of each other versus the troops. … The loyalty card is always going to be scrutinized if you’re going to screw over a fellow officer.”

Because of this secrecy and the manipulation of the justice system, many officers with documented wrongdoing retire with benefits and retain their access to lucrative civilian employment. They become professors at prestigious universities. They hold board positions with defense contractors. And despite their wrongdoing, they are allowed to continue their service to the United States on military justice review panels and speak on behalf of the U.S. Armed Forces.

Some are still on active duty.

“That feeds into the cloak-and-dagger bulls–t,” Montalvo said about the lack of accountability among military officers. “There’s a benefit, but there’s a burden, and the burden sometimes outweighs that benefit. … It’s all f—-d up. That’s why the system needs to change.”

Meanwhile, junior service members — predominantly the enlisted — sometimes have their mental health ignored or weaponized, careers ruined, and reputations left in shambles, often for trivial offenses or crimes committed while in psychiatric distress that was ignored by their leaders.

But there’s a fix — one that could lead to a system service members can trust.

The War Horse spoke with more than two dozen active and retired attorneys, judge advocates, former public affairs officers, junior and senior enlisted, and legal experts from three separate branches and the private sector who said they support a restructuring and growth of the military legal system so it better serves the force.

“The effects of Col. Shaw’s comments — especially to junior judge advocates — will be lasting ones,” said Colby Vokey, a retired Marine defense attorney and Desert Storm veteran.

“Marines will avoid defense billets and won’t make as much noise as they should,” he said. In the military, “billets” refers to job positions. “That ultimately hurts the accused.”

One Marine Corps lawyer left the Marine Corps after filing a whistleblower complaint after seeing too many good lawyers retaliated against with bad performance reviews for defending their clients, he told The War Horse.

The other former Marine judge advocates interviewed for this story echoed similar concerns. “Shaw’s actions were a very clear violation of the rules of professional conduct in the JAG instructions,” said Rob Bracknell, a retired Marine judge advocate, during a phone interview.

“This was definitely unethical behavior. No question about it.”

Bracknell, who now serves as a civilian legal adviser, said the behavior proves military defense is not independent and the government is always in control.

“The courts have been signaling this for years,” Bracknell said. “Every few years, a major unlawful command influence case happens and then nothing really changes. That’s not how it works in other rule-of-law governed societies: Courts issue rulings and people change their behavior as a result.

“But not in the Corps. To me, it reflects a shallow understanding of the solemnity of the officer’s oath,” he said.

“Shaw finally said the quiet part out loud — he gave voice to that which everyone already knew intuitively, but no one would ever admit,” Bracknell told The War Horse. “This idea that they don’t control assignments? That’s simply not true, and I can’t believe any officer involved in the process would have the temerity to deny it.

“This is the smoking gun,” Bracknell said. “This is exactly why the system needs to change.”

A History of Unequal Legal Protections in Uniform

Three years before the colonel’s comments, Capt. Thomas was assigned as the lead military defense counsel for Chief Petty Officer Eric Gilmet, one of three service members — dubbed “The MARSOC 3” — who faced felony charges for the death of a retired Green Beret-turned-military contractor on New Year’s Day at a nightclub in Erbil, Iraq.

Early on Jan. 1, 2019, two Marines and the Green Beret, Rick Anthony Rodriguez, allegedly got in a fight outside the club. The Marines and Gilmet were all members of 3rd Marine Raider Battalion, Marine Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC).

But Gilmet, a Navy corpsman, wasn’t involved in the fight, his lawyer Colby Vokey told The War Horse during a series of interviews. Instead, he provided medical aid to the injured veteran at the scene of the fight, and found — based on his years of extensive trauma and emergency medicine training — that the injured man did not need treatment at a hospital.

Then Gilmet and the two Marines escorted Rodriguez to the nearby military base where the corpsman continued to monitor the veteran’s vital signs. He checked the injured man’s blood oxygen levels using a pulse oximeter. He applied Dermabond, an adhesive for lacerations, to the back of the veteran’s head. After a few hours of monitoring Rodriguez, the corpsman left a civilian contractor in charge and went to bed.

An hour later, the contractor barged into Gilmet’s quarters nearby and told him the injured veteran was not breathing. The contractor ran for help while Gilmet started CPR. Moments later, help arrived and Gilmet continued CPR in the back of a pickup truck as they drove to the hospital, Vokey said.

Three days later, Rodriguez died after being flown to Germany for treatment.

A medical examiner ruled the cause of death as blunt force injuries to the head, which has been disputed by experts and the treating physicians, Vokey said.

Military prosecutors charged Gilmet and the two Marines — Gunnery Sgts. Joshua Negron and Daniel Draher — with involuntary manslaughter, negligent homicide, obstructing justice, and violations of orders.

The sentence carries a potential of at least a 20-year term and felony convictions that would strip the men of their honorable discharges and not only their military retirement but lifelong access to education, housing, and medical benefits.

But the details about the sailor’s involvement led many experts to question why the corpsman was being charged with a crime at all.

Since Gilmet’s arrest, attorneys and elected officials have alleged in the media and press releases that an overzealous chain of command is more committed to making an example of the accused than ensuring a fair investigation and trial.

At the start of a December 2021 hearing, the military judge addressed the conflict of interest, according to reports published by UAP, a group that advocates for service members accused of crimes. In his later findings, the judge conceded that Col. Shaw’s comments last fall represent unlawful command influence and, therefore, violated a statute or the defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel that is free of conflicts of interest.

The prosecutors then described the colonel’s comments as “misguided and ignorant” and “not grounded in reality,” according to the report. “Due to Shaw’s dangerous comments, Chief Gilmet has lost trust and confidence in the military justice system and now has doubts about Captain Thomas’s ability to effectively represent him without fear of reprisal.”

That December day, after representing Gilmet for three years — and after Capt. Thomas turned down an opportunity to serve as a special assistant United States attorney so he could remain as Gilmet’s senior defense counsel — the judge who oversaw Gilmet’s case granted the sailor’s request to fire Thomas and his team. Thomas did not respond to multiple interview requests.

“It was a Hobson’s choice,” Gilmet explained in his affidavit. “I could keep military defense counsel who had a conflict and whose representation was being influenced by Colonel Shaw’s comments and the possible impact of that representation on their careers.

“Or I could agree to release the two military attorneys who I had trusted completely and had spent considerable time preparing me and the case for trial.”

The combat veteran was awarded and credited with saving Marines on the battlefield. The trial, he wrote, was worse.

“These last several years have been the scariest of my life,” Gilmet wrote. “But I took comfort in the fact that I had Captain Thomas and Captain Riley there to defend me and ensure I received a fair trial.

“I don’t believe that a fair trial is possible any longer.”

The Corps’ “Black Book”

While enlisted service members like the MARSOC 3 are paraded through the justice system often just to dissuade misconduct in the ranks, Marine Corps officers are tracked in a deeply protected journal called the Officer Disciplinary Notebook.

Inside the notebook, all investigations of and crimes committed by officers are kept meticulously tracked — and often omitted from the official record and congressional disclosures — throughout their careers, highlighting a mix of favoritism and “Sugar Daddy deals” overseen by military lawyers and senior officers, according to multiple senior enlisted Marines and officers who have read through its contents.

High-ranking Marines, who spoke on the condition of anonymity in fear of reprisal, said the behaviors are well-known by both current and past commandants.

“Where there is a hang-up is on the decision whether to put someone on the Officer Disciplinary Notebook in the first place,” a senior military attorney familiar with the notebook and its use told The War Horse.

“Commanders will often try to shield those they like from having to go on it, even though the plain reading of the requirement says they should.”

Dubbed The Black Book, the notebook houses decades of information about investigations of and convictions for misconduct, results of command climate surveys, and documents pertaining to any other derogatory information gathered throughout an officer’s career, often without their knowledge.

It’s overseen directly by the staff judge advocate to the commandant of the Marine Corps, according to senior military attorneys.

“The Officer Disciplinary Notebook (ODN) is an internet-based electronic database used to report and track cases of Marine Corps officer misconduct and substandard performance,” Stenger, the Marine Corps spokesman, explained. “The ODN exists principally to inform the promotion process.”

Two Marines who worked directly alongside the commandant, a sergeant major with decades in uniform, and two field-grade officers who once had access to the ODN said that wrongdoing is frequently omitted, manipulated, and weaponized by the Corps’ senior officers both for the benefit and at the detriment of Marine officers when they discuss individual Marines’ careers and promotions outside the official promotion board process.

The abuse represents a clear and systematic imbalance of justice for the accused and blatant unfairness in the assignment and promotion process, a senior Marine defense attorney and five other Marines familiar with the notebook told The War Horse.

“Instead of it helping them — instead of it being a tool that protects the honor and integrity-driven system that we want to believe is there — instead it becomes a tool of miscreants who use it to favor their friends, protect the ones they like, and for guys who get left on there a little longer, it hurts them going into a [promotion] board,” said a senior Marine attorney familiar with the notebook’s use.

The notebook’s contents have long been kept secret from junior officers and the enlisted ranks, said a high-ranking Marine who perused its trove of wrongdoing at length. And the public would be outraged — and the Corps’ reputation for integrity and honor would be tarnished — if the notebook were published and the true behaviors of its officers revealed, multiple Marines said. Five Marine officers familiar with the ODN agree.

“It would also shed a light on the people who decided to just make it a book entry as opposed to telling someone they need to go or they need to be subjected to a court martial,” said Kevin McDermott, a retired Marine judge advocate and civilian defense attorney. “This is an ongoing effort to keep appearances up as to the upper echelons of officer leadership. You’re only seeing a fraction, I’m sure, of the misconduct in the officer corps.”

The notebook also gives the Corps’ most senior officers the ability to keep dirt and tip the scales to ensure a “company-man culture” where Marines are hesitant to speak out against wrongdoing and abuses of power by their leaders, the five senior Marines said.

The notebook allows leaders to abandon the service member to protect the institution from embarrassment or being held accountable for its actions.

“The favorite sons will never be hung out to dry,” a senior Marine said.

This lack of accountability and integrity drives talented attorneys from the military and costs incalculable amounts of taxpayer money while jeopardizing U.S. national security.

“I’ve had to tell a battalion commander no, I wouldn’t ‘fix it’ when he ordered an illegal search and had the sergeant major call it a ‘health and comfort inspection,'” said a Marine judge advocate.

Many of the behaviors and crimes detailed in the notebook — which include a plethora of scathing details about active duty and retired general officers — are the same behaviors the Corps wants hidden from the public, the five senior Marines said.

Sex crimes. Racism. Extremism. Alcoholism. Domestic violence.

The notebook has it all.

“There are senior Marines with lists of inspector general complaints as long as your arm,” one Marine said.

A System of “Legal Smoke and Mirrors”

Previous protests of the system have gone largely unnoticed.

In 1984, McDermott was a 28-year-old military defense counsel-turned-whistleblower who revealed that the Marine Corps routinely retaliated against zealous defense attorneys by giving them bad performance reviews.

But 18 months earlier, McDermott had just begun his career as a military attorney when he was assigned to court-martial cases just days after arriving at his first duty station. Within his first few months, he maintained an average caseload of 30 to 40 clients that ranged from rape and espionage to drug trafficking and homicide.

McDermott often worked nights and weekends to catch up on cases. The legal offices had holes in the walls and the electricity barely operated. There were no functioning heaters in the defense offices and the attorneys shared only one typewriter to prepare their case files. Defense attorneys had to buy their own. No case-management system existed.

“I would imagine … a young kid facing charges for the first time in his life walking into that building was absolutely depressed about his chances, because the building gave you that kind of vibe,” McDermott said. “It was literally that interrogation light that hung over right in the middle of the damn room.”

But McDermott wasn’t alone in his frustrations. His fellow attorneys struggled to keep up with the workflow and were denied opportunities for professional development. As a result, he saw qualified, promising attorneys leave active duty because of the hypocrisy in the military judicial system.

“We were always told to not slow the choo-choo train down — to keep it moving,” McDermott said. “You were quite often pressured into presenting cases when you could’ve used more time to prepare.” Four decades later, a defense attorney told The War Horse that they are told to “keep the chow line moving.”

One thing was obvious from day one: There was an imbalance of power and widespread hypocrisy among military leadership, McDermott told The War Horse. Active-duty attorneys say the same problem exists today.

And if any of the junior lawyers complained, their careers were ruined.

“A lot of these guys and gals suffered in silence,” McDermott said.

For 18 months, McDermott kept his head down and did as he was told, he said. But throughout his first years in the Corps, the behaviors he witnessed made him question whether he wanted a career in the Marines. He wondered if he should speak out against systemic issues.

McDermott moved from attorney to whistleblower when the Marine Corps fired him from the defense shop. His offense? He had won an accidental shooting case, an accomplishment in any other legal office. But the commander had wanted three Marines “crushed” for their willful negligence, McDermott said.

Before he got back to his office, all of his belongings had been removed.

After McDermott’s firing in 1983 and after he had filed his formal complaint, the Marine Corps conducted an internal investigation. They whitewashed the behaviors that led to his dismissal. But the coverup inspired other defense attorneys to step forward. Soon, national media attention led to outrage among lawmakers, service members, and civilians alike.

After the Marine officers banded together to speak out, the commandant deemed the initial investigation as “woefully inadequate,” and lawmakers ordered a third-party investigation, McDermott said. Had the whitewashed investigation not been challenged, the truth might have remained hidden from the public.

“There’s always strength in numbers,” McDermott said.

The investigator’s final report verified the patterns of wrongdoing. By the end of the year, the Marines established a command for defense counsel that was independent from the prosecutors’ office.

But while the new command led to some improvements in military defense and helped to ensure a more fair trial, McDermott’s career was ruined.

To make matters worse, the changes to the military’s criminal justice system weren’t radical enough to afford service members the same legal protections as the civilian citizens they serve, he said.

“It was the watershed moment that forced a bunch of people out of the Marine Corps and forced a bunch of changes,” McDermott said. Still, he mourns that they didn’t do enough with the momentum they’d gained.

The young attorneys didn’t understand the power they had to make further progress — to force justice on the good ol’ boys’ system.

“We were young and naive. We had the bull by the horns and didn’t know what to do with it.”

“You Really Run the Risk of Ruining Someone’s Life”

Experts like McDermott say Congress should have stepped in long ago to make the necessary changes to protect military defense lawyers from being punished for vigorously representing their clients.

That rampant disregard for the rights of the accused — as well as how it reinforces a twisted definition of justice — drove McDermott from active duty to a career as a civilian defense counsel in military cases. Since then, his work has led to convictions of service members being overturned, mistrials being declared, and murder charges being dismissed.

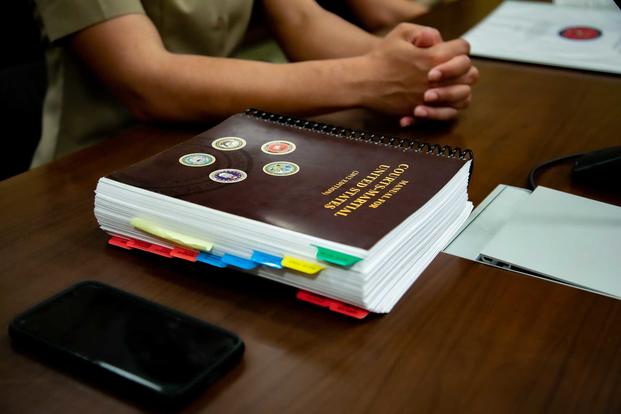

For years, lawmakers and veterans of the military justice system have advocated for changes to the Uniformed Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) that would strip commanders of their involvement in criminal proceedings and allow for more equal protections for service members.

The last major modifications to the system came in 1968, 1984, and 2016. More recent amendments have focused on cyber and sex crimes. In 2021, the Defense Department, following orders from lawmakers, launched its efforts to allow attorneys to specialize in sex crimes. Experts say the changes fall short of what’s truly needed to effect change.

There have been improvements to transparency, bit by bit, but the justice system in the military as a whole has not been modernized since the UCMJ was enacted in 1950. That came after outrage in Congress that millions of service members had been court-martialed during World War II under draconian military tribunals.

Today, nearly four decades after McDermott and his fellow Marines first blew the whistle by filing an internal complaint to the military in 1984, the lack of protections for service members remains widespread — a proclivity often validated by the Supreme Court because of the Fifth Amendment. The Fifth Amendment states that a person’s right to a grand jury disappears “in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger.”

But a system that takes advantage of a law meant to protect U.S. citizens to instead punish its own isn’t the only problem. As the country discusses improvements to state and federal criminal justice systems, the military has largely been left out of that conversation. And lawmakers are in a stalemate about how exactly to change the military’s legal system.

“The community clings to this cultural dogma without questioning whether reasonable alternatives exist or exceptions could be made,” said a judge advocate who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal.

“Just as the Marine Corps itself suffers from institutional paranoia, the Marine Corps legal community suffers from insecurity about being disliked because of being overeducated and having to be the moral compass both in garrison and on deployment,” he said.”I personally see that specific function as the greatest value Marine lawyers can add,” he said.

Military defense offices are under-resourced, like state public defenders. And they don’t have adequate access to investigators who may strengthen the defense of the accused, according to multiple sources interviewed during this investigation.

Paired with inexperienced and burned-out military police investigators, many active and retired military attorneys said the deck has remained stacked against the accused for decades.

“I just think they’re overwhelmingly incompetent,” said Bracknell, the retired Marine attorney who is a senior legal adviser to an international organization. “I don’t think they’re trained to the same standard as other similarly positioned law enforcement. Military police are not real police — they’re traffic cops.”

The Marine Corps is not the only service that needs an update.

When it comes to working with the Army Criminal Investigative Division or Naval Criminal Investigative Service, he’s had more bad experiences than good with them, Bracknell said. Multiple other attorneys agree.

“Some of their agents are pretty good, but some others are just buffoons,” he said. “I’ve had a supervisory special agent at a major installation tell me that once he identifies a suspect, he stops pursuing other leads. That’s wildly wrong. Outside the military gate, investigators are light-years ahead of NCIS.”

As things stand, there isn’t much hope for change: The majority of cases are not eligible for an appeal to the Supreme Court.

And Congress relaxed prohibitions that restricted retired military attorneys from being appointed to positions on the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. That changed in 2014 because of the National Defense Authorization Act, which authorized a waivable seven-year cooling-off period.

The exemptions are similar to those authorized for retired Gens. James Mattis and Lloyd Austin to be appointed as the last two secretaries of defense.

“It’s supposed to be a civilian court, but there’s a hell of a lot of military experience there,” said Eugene R. Fidell, who teaches military justice at NYU Law School. “It’s gotten away from the Senate, which confirms the judges, and it’s gotten away from the Department of Defense.”

Other military attorneys agree.

“We didn’t advocate as strongly as we should have for more aggressive changes to the way the military does things,” said McDermott, who has spent decades as a defense counsel in military cases since retiring from active duty.

“We are long past an indigent person being required to defend themselves, but when you have a junior lieutenant or young captain leading a serious felony case and they don’t have the experiences or resources they need, you really run the risk of ruining someone’s life.”

Military Attorneys Disregard Precedent and the Rule of Law

Experts say the flaws in the military justice system begin long before a case ever goes to trial: A defendant can be charged with a career-ending crime from baseless allegations that often would not stand up in a civilian court.

And if that case goes to trial, unlike a civilian court where a jury pool is random, the service member’s commander selects the panel of jurors, who are referred to as members in the military.

“You don’t get a jury of your peers,” a retired military defense attorney told The War Horse. “It’s all about control.”

In 2017, a Marine named Lance Cpl. Emmanuel Q. Bartee faced larceny charges and was subjected to three separate court proceedings because the chain of command overseeing the case repeatedly manipulated member selection. In each instance, despite being informed of the problematic panel selection, the general who oversaw the case ignored the recommendations and did not modify the member list, Bartee alleged.

A majority of the judges on the military judicial system’s highest court disagreed with Bartee. In a dissenting opinion, Chief Judge Charles Erdmann wrote that “to uphold the essential fairness and integrity of the military justice system I would set aside the findings and sentence and remand the matter for a rehearing with a properly selected panel.”

That same year, a case involving a Marine named Sgt Dexter K. Kunishige, who was convicted of child sexual assault and pornography, was tainted for the same reason. The Navy and Marine Corps Court of Appeals opined that commanders cherry-picked members of the jury panel. And they repeatedly failed to disclose crucial information about the actions of the general overseeing the case. They also found that, had adequate disclosures been made, at least one jury member would have been removed for implied bias.

As a result, one of the judges wrote in a 2021 opinion that a “cavalier” attitude “permeated the discovery of materials related to the member selection. It is clear the Government was uninterested in making timely production of the member selection documents sought by the Defense and ordered by the military judge.”

That judge also cited Erdmann’s dissent in the previous case six months earlier. Following another court-martial process, Sgt. Kunishige was dishonorably discharged and sentenced to 30 years of confinement in a military prison. The case is pending appeal.

“I would humbly submit that our superior court should revisit [the precedent] before panel stacking becomes the norm against our Marines and Sailors,” a judge on the panel wrote in their summary.

Following a conviction, only cases that result in a bad conduct or dishonorable discharge, or where a sentence exceeds certain thresholds of confinement, must have an appellate review. And because only appellate cases are publicly available, details of lesser crimes and misconduct are not visible to the public. This covers up failures to address mental health, hides life-altering punishments from taxpayers, and denies service members justice.

Most troubling is that the majority of punishments in the military are not visible to the public because they are handed out by a commander, who acts as judge and jury, rather than through a court-martial. This process is known as non-judicial punishment or NJP — as well as “Article 15” or captain’s mast, depending on the branch of service.

“It’s a way of playing that loyalty card,” a senior lawyer said. “There’s a wicked psychological game there. It’s a way to control things and keep things out of the press.”

Because each of the charges is classified as a personnel matter — many leading to career-ending and life-altering punishments and ramifications — they are not discussed or released by officials.

“Headquarters Marine Corps does not track NJPs at the service level,” said Maj. James Stenger, a spokesperson for the Marines.

“It disappears like smoke,” a senior lawyer said. “I don’t trust it, to be blunt.”

A System of “Legal Smoke and Mirrors”

Col. Shaw’s statements to a room of Marine Corps lawyers speak of more than a single instance of abuse: They point toward a closed culture that goes unchecked by Congress. This, experts say, has allowed the Corps’ insular legal system to metastasize into a penal system ripe for abuse, assumptions about motives, and manipulation.

Throughout the entire legal process, Marines adjudicate other Marines: The attorneys. The judges. The security guards. The police. The investigators. The courtroom and administrative staff. The commanders. And the general who can modify the judge’s decision in some cases, but only to the benefit of the accused.

All Marines.

“The entire Marine Corps judge advocate community is hopelessly f—–g broken,” said a retired judge advocate who spent more than 20 years in uniform. “It’s a good ol’ boys club.”

Good Marines don’t stick around in bad systems. And the civilian world offers better pay for lawyers. For years, public reports have shown “unhealthy” staffing and retention levels that are leading to burnout among young officers, who then leave the service in droves. Making the problem worse, bad policies in the Defense Department are hurting the Corps’ ability to train and retain qualified attorneys.

Worse yet, the accused have little recourse. The military denies service members accused of crimes some of the most basic legal protections guaranteed to civilians by the Constitution — the right to a unanimous verdict and the potential to appeal their case to the Supreme Court — say experts, veterans, and attorneys across the Defense Department.

And in the event of prosecutorial misconduct or a conviction being overturned, service members and veterans, unlike civilians, cannot sue the government for wrongdoing during legal proceedings.

“That whole servant-leader thing that Gen. Lejeune talked about is out the window,” said a retired sergeant major with 30 years in uniform. “That s–t doesn’t apply anymore, you know. It’s all about moving up and getting that next star and padding that retirement check.

“And meanwhile, up at the very top, they’re just doing whatever they want, treating people however they want, administering justice how they feel like it, and finding excuses for bad behavior to try to make it go away.”

Whether a Marine is punished or not falls on the shoulders of the Corps attorneys who themselves are not required to follow myriad civilian best practices.

In spite of this incredible autonomy and responsibility, no functioning system of accountability exists to hold Marine attorneys responsible for the failures or negligence, despite being commissioned by Congress to pursue justice for the service members accused of crimes.

“The inspector generals do not exist to find misconduct,” the sergeant major said. “They look for other reasons to excuse poor behavior.”

The Corps’ legal system operates on trust. The basis of that system, by default, is its courts, experts say.

Lawyers influence everything in the Corps: The internal and external reports. The recruiting ads. The enlistment waivers. The gear purchases. The press releases. And interviews with the media. It’s all reviewed by Marine attorneys.

The two senior spokespeople for Headquarters Marine Corps, Brig. Gen. George Rowell IV and Col. Kelly Frushour, did not respond or declined interview requests to discuss all aspects of The War Horse’s investigation and why it seems Marine Corps officers are not held accountable for all wrongdoing.

The staff judge advocate to the commandant of the Marine Corps, Maj. Gen. David Bligh, and Col. Valerie Dalyluk, the chief defense counsel in the Marine Corps, did not respond to requests to discuss the issues impacting the Corps’ legal community and its willingness to adhere to the rule of law.

When asked for his perspective as the Corps’ senior representative for enlisted Marines, Sgt. Maj. Troy Black, the sergeant major of the Marine Corps, declined to be interviewed.

When given the opportunity to provide confidence in the fairness and effectiveness of the system, Gen. David Berger, the commandant of the Marine Corps, did not respond to multiple interview requests.

“Don’t Marines pride themselves on integrity?” many of the Marines asked during conversations about the details of The War Horse’s investigation.

The Marines spoke with The War Horse on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation. One’s reputation within the Marine Corps community can influence civilian opportunities beyond active duty.

“These officers have a responsibility to take care of the Marines,” one said. “Period.”

A senior defense attorney on active duty agreed and said Marine Corps leadership has a responsibility to discuss these issues in the media.

“Gen. Bligh needs to answer for the community,” said a Marine defense attorney, adding that Bligh needs to “answer for how he’s going to protect and insulate the defense counsel” going forward.

“The commandant is required to and is responsible for ensuring that the military justice that occurs within his branch is done so fairly and effectively and that defense counsel are valued for the work that they do,” the Marine officer said.

“The fact that they haven’t commented — Gen. Bligh and the commandant — will leave the force wondering if what Col. Shaw said was correct.”

Trust in the System Can Be Restored

The veil of secrecy in the military’s two-tiered legal system allows attorneys to ruin lives — both officers and the enlisted — often without consequence

In one of the rare instances where a civilian federal judge in one of the country’s most influential trial courts reviewed a Marine case, she penned a scathing criticism of how the commanders and attorneys were unfaithful in their pursuit of justice.

“It is not a tale that inspires confidence in our criminal justice system,” wrote the judge, Colleen McMahon, now retired from the Southern District of New York.

“The real JAG [judge advocate] dropped the ball, and did so deliberately, not accidentally or inadvertently — even though the Department of Defense was prepared to fight a turf war with the Department of Justice to keep the case within the military.”

Active-duty and veteran Marine attorneys say they worry most that the current commandant, Gen. Berger, tolerates and trusts a legal system that has grown so corrupt — so brazen and unregulated — that for nearly eight years, the leadership of his Judge Advocate Division felt emboldened to violate a direct order from his predecessor to launch a study that could have identified a more fair justice system that Marines and the public could fully trust.

“I wouldn’t hang this only around Gen. Berger’s neck,” said Bracknell, and added that decades of commandants, who all bear responsibility for ignoring the flaws in the Corps legal system, “have all been asleep at the switch.” As a result, the problem has festered.

“They’re so focused on their day jobs that they forget that disciplining the force is a big deal and leadership through fair treatment is a big deal,” Bracknell said.

Moving forward, experts say there is only one solution: accountability.

By taking proactive steps to increase independence, transparency, and oversight, the Corps and Defense Department can prevent improper influences on criminal proceedings, foster greater trust in the legal system among service members, and improve transparency with the public, experts say.

“We’re moving backward with less and less rights for the accused,” said a Marine judge advocate with more than 20 years in uniform. “The current system is concerning.”

Taking initiative to improve the system and trust in it among service members will encourage more victims of crime to step forward, cause lawyers to more zealously defend against false allegations, and create more rigorous investigations that will decrease acquittal rates. It will also maintain good order and discipline in uniform, and strengthen both recruiting and retention efforts, they said.

The Corps cannot be trusted to do this on their own, they said. Its most senior leadership has ignored the problem for too long, and lawmakers must step in.

“They need to step in with expertise and identify the right problems, not just the most politically expedient problems,” Bracknell said, adding that while recent reforms have rightly focused on addressing sexual assault in uniform, the same attention should be shown for the rights of the accused.

“No one is really interested in really fixing the system,” he said. “The courage that [elected officials] showed in 1950 when they completely remade the system, that was different. That was special. You could never recreate it from scratch right now — not in this environment.”

Until Congress takes decisive actions, senior military leaders will continue to manipulate the system, critics say. General officers and attorneys who should ensure that integrity — one of the Corps’ 14 leadership traits — is the backbone and lifeblood of the Corps’ legal system instead use it for their own purposes.

As a result, bulletproof rape cases are thrown out for intolerable delays. Commanders are allowed to manipulate the selection of members to the jury panel. And testimony from incompetent witnesses has been allowed. Marines have been convicted — and later released — for false, unsubstantiated allegations and legal failures.

Because the military is struggling to retain its most talented attorneys, inexperienced officers are being assigned to felony cases, and judges are reducing sentences to avoid public scrutiny and mandatory appellate review. In an ongoing investigation at Camp Lejeune, a major is being investigated for what Shaw himself described during the November 2021 meeting as “absolutely unacceptable” behaviors at multiple duty stations. They allegedly include “intentionally or negatively” manipulating the timelines of sexual assault cases to force military generals to accept pretrial agreements with minimal accountability for the accused.

Military officers are hiding wrongdoing from citizens, attorneys say.

Most troubling, the military’s own records reveal that the lack of integrity in the military justice system has allowed for a decades-long pattern of unlawful command influences to occur during criminal proceedings — from junior officers to a former commandant.

Trust in the legal system and its leaders has eroded, experts say.

“Active-duty Marines aren’t speaking up because our institutional culture in the Marine Corps demands extreme deference to authority, rewards conformity, and punishes candor,” wrote retired Maj. Charles M. Olmsted for The Wall Street Journal in March following a scathing editorial by former secretary of the Navy and decorated Marine Officer Jim Webb about the future of the Marine Corps.

“The Marine Corps selects those who provide the answers that the boss wants to hear. The most important leadership traits are tact and loyalty — to one’s boss. The result is an organization that can’t render an honest and compelling justification for any major initiative.”

Meanwhile, service members who have demanded accountability for failures ranging from sexual assault investigations to general officer misconduct and the Afghanistan withdrawal — where 11 Marines, a Navy corpsman, and a soldier died as a result of massive planning and strategic failures — have been silenced. Service members are often discarded to solitary confinement in the brig where they are left to beg military judges for mental health care during failed pursuits of justice, attorneys say.

The system plays against everything for which the U.S. Armed Forces stands.

And it ruins people’s lives.

This War Horse investigation was reported by Thomas J. Brennan, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Ben Kalin, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter

Show Full Article

© Copyright 2022 The War Horse. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Tags: Black Book Daddy Deals Deny Justice Marine Corps Marine Corps News Members Military Service Sugar Working Warriors